Human-in-the-Loop Agents: when to require review, when to automate, how to log decisions

Agents are moving from “answer questions” to “do work”: filing tickets, changing settings, running scripts, editing content, deploying changes. That shift is less about model quality and more about agency—the ability to take actions in real systems.

The catch is simple: the moment an agent can act, you inherit the failure modes of automation and the ambiguity of language. “Human-in-the-loop” isn’t a conservative stance. It’s how you ship useful automation without creating trust debt.

This post is for developers and tech leads building agentic features (internal or customer-facing). It’s a practical framework for three decisions:

- when an agent should require human review

- when it’s safe to automate end-to-end

- what to log so you can debug and audit what happened later

1. Why human-in-the-loop is still the default

Most agent failures aren’t dramatic. They’re quiet:

- the agent “helpfully” changes the wrong thing

- it makes a reasonable assumption that’s false in your environment

- it completes the task, but violates policy or expectations

- it leaves no trace, so nobody can reconstruct why the change happened

Humans are still the best system for:

- interpreting ambiguous intent

- spotting context mismatches

- deciding when a “correct” action is still the wrong action

The goal isn’t to keep humans forever. It’s to earn automation by proving reliability in narrow lanes.

2. The decision framework: review vs automate

To decide whether an agent needs review, start with two axes: risk and reversibility.

Risk (what’s the worst credible outcome?)

Risk is high when actions touch:

- money, billing, or payments

- permissions, roles, access control

- production config, deployments, or infrastructure

- destructive operations (delete, revoke, purge)

- regulated or sensitive data (PII, health, finance)

Reversibility (can we reliably undo it?)

Reversibility is high when:

- changes are versioned and can be rolled back

- actions are idempotent and replay-safe

- side effects are contained (single tenant, scoped resource)

- “undo” is real, not theoretical

A practical rule of thumb

- High risk + low reversibility → require review (and often double-confirmation).

- Low risk + high reversibility → automate (with guardrails and logs).

- Everything else → start with “suggest” (agent proposes; human applies).

If you’re operating in regulated or safety-critical contexts, treat “human oversight” as a first-class product requirement, not an implementation detail. The EU AI Act explicitly calls out human oversight measures for high-risk AI systems, including preventing over-reliance and enabling interruption/override. That expectation is becoming the norm, even outside the EU.

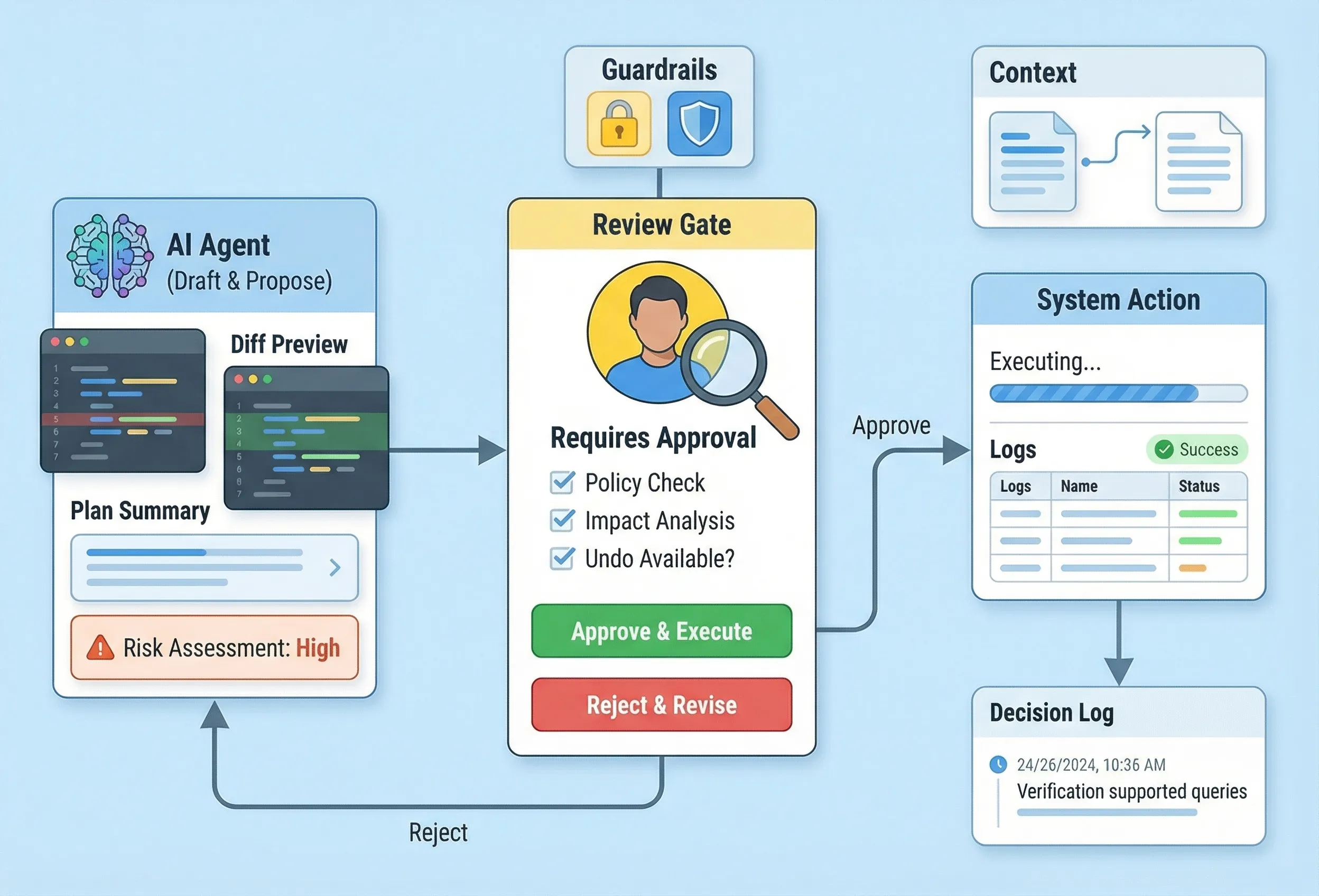

3. A tier model that scales: Draft → Suggest → Execute

“Human-in-the-loop” shouldn’t mean “a human approves every tiny step.” You need tiers.

Tier 0: Draft

The agent produces artifacts, not actions:

- a proposed plan

- a PR description

- a set of test cases

- a change summary and risk assessment

Humans execute separately. This is the best default when you’re learning what the agent gets wrong.

Tier 1: Suggest

The agent proposes an action plus a diff (or a concrete preview), and a human clicks “apply”.

This is where most useful agent work lives for a long time because it scales trust:

- the agent does the tedious synthesis

- the human makes the irreversible decision

Tier 2: Execute with approvals

The agent can execute, but must pass approval gates based on risk:

- “safe” operations run automatically

- “risky” operations require explicit approval

- “very risky” operations require two-person review or a protected role

Tier 3: Execute autonomously (narrow lanes only)

Autonomy is earned in low-risk, reversible workflows with strong observability:

- auto-triage and labeling

- formatting/lint fixes

- updating dashboards/reports

- summarizing and routing issues

If you can’t clearly define the lane boundaries, you’re not ready for Tier 3.

4. Approval UX patterns that keep humans fast (not annoyed)

Bad approval UX turns human oversight into a tax. Good approval UX turns it into a power tool.

Patterns that work:

- Show the impact, not just the action. “This will revoke access for 12 users” beats “Update role.”

- Show the diff. Humans approve diffs, not intentions.

- Make the safe choice the default. Preselect “review changes” over “run now” when risk is unclear.

- Confirm at decision points, not every step. Batch low-risk steps into a single approval.

- Build a real undo. If rollback is possible, surface it as a primary recovery path.

If you only implement one UX feature: implement cancel + stop that actually halts ongoing work.

5. What to log (minimum viable decision logging)

If an agent can act, you need logs that answer:

- what goal was the agent pursuing?

- what inputs and context did it use?

- what did it decide, and why?

- what actions did it take?

- who approved what, and when?

- what happened after (success, partial failure, rollback)?

A practical minimum set of fields:

- Identifiers:

task_id,trace_id,user_id,agent_id, timestamp - Intent: user goal, requested action, constraints/policies applied

- Context: retrieved sources (links/ids), tool inputs, environment (tenant/project)

- Decision: proposed plan, uncertainty/assumptions, risk level, required approvals

- Execution: tool calls (name + parameters), diffs/patches, external IDs (ticket/PR/deploy)

- Approvals: approver(s), approval scope, time, reason

- Outcome: status, errors, rollback/undo actions taken

A small schema you can steal

{

"task_id": "agt_2025_11_18_0142",

"trace_id": "b9d2c4e3...",

"timestamp": "2025-11-18T01:42:11Z",

"actor": { "type": "agent", "id": "support-agent-v3" },

"requested_by": { "user_id": "u_123", "role": "admin" },

"goal": "Disable feature flag for tenant acme-co",

"policy": { "risk": "high", "requires_approval": true },

"context": {

"tenant": "acme-co",

"sources": [

{ "type": "doc", "id": "runbook_17", "uri": "…" },

{ "type": "ticket", "id": "OPS-4412", "uri": "…" }

],

"assumptions": ["Flag exists in prod and is safe to disable"]

},

"proposal": {

"summary": "Disable FLAG_X for tenant acme-co",

"diff_preview": "flags/tenants/acme-co.json: FLAG_X true → false"

},

"approval": {

"status": "approved",

"approved_by": "u_987",

"approved_at": "2025-11-18T01:43:02Z"

},

"execution": [

{ "tool": "flags.update", "params": { "tenant": "acme-co", "flag": "FLAG_X", "value": false } }

],

"outcome": { "status": "success" }

}

This is not bureaucracy. It’s what lets you debug “why did the agent do that?” without guesswork.

6. Uncertainty is a first-class state (design it explicitly)

Agents will face unknowns: missing context, conflicting sources, ambiguous requests.

Your system should:

- require an Assumptions section for any non-trivial plan

- block execution when assumptions touch risk (permissions, money, destructive actions)

- ask one clear question to proceed (not a vague back-and-forth)

If you don’t design uncertainty states, you get the worst outcome: confident execution on shaky ground.

7. When it’s safe to automate (good candidates)

Good automation candidates share the same traits:

- low risk

- reversible

- bounded scope

- easy to verify

Examples:

- formatting and lint fixes (with diffs)

- generating test skeletons (humans decide what to keep)

- summarizing issues and clustering duplicates

- preparing PR descriptions and changelog drafts (not publishing)

- routing support tickets to the right owner

If a human can verify correctness in under a minute, it’s often a good lane to automate first.

8. When not to automate (high-risk lanes)

Avoid autonomy (or require strong approvals) for:

- payments, refunds, billing changes

- permission changes, user provisioning, access revocation

- destructive operations without undo

- production deploys/config changes without a protected workflow

- anything involving secrets or credential movement

- decisions with legal/compliance consequences without explicit sign-off

If you must automate in these lanes, you need narrow scopes, two-person review, and aggressive monitoring.

9. Guardrails that prevent “agent drift”

Guardrails are what make automation safe at scale:

- Least privilege tools. Give the agent only the actions it needs, not a general admin key.

- Parameter bounds. Limit the size/scope of each action (max records, max tenants, allowed environments).

- Dry-run and diff-first defaults. Prefer proposals and previews unless the lane is explicitly safe.

- Stop conditions. Timeouts, error thresholds, and “halt on anomaly” rules.

- Sandboxing. Test actions in non-prod or isolated environments when possible.

- Continuous evals. Regression tests for agent behavior, not just code correctness.

If you treat guardrails as “later,” you’ll end up shipping a powerful feature you can’t safely expand.

10. A rollout plan that earns autonomy

A practical path that works in real teams:

- Start in Tier 0 for a single workflow. Measure where the agent is wrong.

- Move to Tier 1 with diff-based suggestions. Track approval time and override rate.

- Introduce Tier 2 approvals only after you can reliably classify risk and reversibility.

- Grant Tier 3 autonomy only to narrow lanes with strong undo + observability.

If you do this well, “human-in-the-loop” stops being a debate and becomes a deployment strategy.

Conclusion

Human-in-the-loop agents aren’t a compromise—they’re how you ship agents that people actually trust. Decide review vs automation using risk and reversibility. Use tiers so humans spend attention only at real decision points. And log decisions like you’ll need to explain them later—because you will.

If you can’t reconstruct what happened from your logs, you don’t have an agent. You have a mystery.